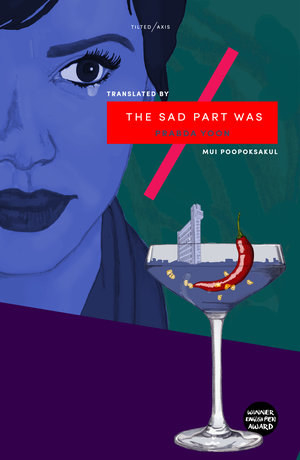

Prabda Yoon, The Sad Part Was, Trans. by Mui Poopoksakul, Tilted Axis Press, 2017.

Includes the stories:

Pen in Parentheses

Ei Ploang

The Disappearance of a She-Vampire in Pattaya

Winner of a PEN Translates! grant. Selected as a 'book to look out for in 2017' by The Guardian and BuzzFeed Books. In these witty, postmodern stories, Yoon riffs on pop culture, experiments with punctuation, flirts with sci-fi and, in a metafictional twist, mocks his own position as omnipotent author. Highly literary, his narratives offer an oblique reflection of contemporary Bangkok life, exploring the bewildering disjunct and oft-hilarious contradictions of a modernity that is at odds with many traditional Thai ideas on relationships, family, school and work.

‘Evocative, erudite, and often very funny stories of Bangkok life.’— The Guardian

‘Formally inventive, always surprising and often poignant, with the publication of this fluid and assured translation of The Sad Part Was, Prabda Yoon can take his place alongside the likes of Ben Lerner and Alejandro Zambra as a writer committed to demonstrating that there’s life in the old fiction-dog yet.’— Adam Biles

‘An entrancing and distinctive collection. Yoon’s limpid prose faces up to large, transcendental questions, all the while flickering with beautiful other-worldly images and flashes of deadpan humour.’— Mahesh Rao

Prabda Yoon is one of Thailand’s finest writers. These witty, adventurous, and wholly brilliant short stories were a necessary shot across the bow when they first appeared in Thai, a deceptively revolutionary collection that helped to transform the country’s literary landscape. Long deemed untranslatable, given their interests in linguistic wordplay, their appearance in English—in this supple, agile translation by Mui Poopoksakul—is a cause for celebration.’— Rattawut Lapcharoensap

A humble traveller discovers a monumental secret from outer space in the forests of southern Thailand. A vampire named Rattika goes missing in Pattaya. A couple engaged in an extramarital affair witness the death of a man crushed by fragments of an advertising sign (they are playing Twister when this happens; the killer debris spells “N” “O”). Elsewhere, a mother in Bangkok strives to save enough money to take her troubled son to Alaska to see snow, and a young man obsesses over the loss of buttons on his shirt.

The stories that form Prabda Yoon’s mind-bending and strangely melancholic universe are unfailingly provocative, both in their choice of subject matter — there isn’t a single dramatic situation that can be said to be conventional in the collection of 12 stories — as well as their narrative form. Protagonists cede their place to a chorus of casual acquaintances, or else rebel against their creation by addressing the reader directly; heroes are also anti-heroes; plot lines streak ahead but are deliberately thwarted; the writer Prabda Yoon even appears in one of the stories. Despite their playful, coolly surrealist wrappings, however, the stories are built around more solidly old-fashioned notions of displacement and loss, with people struggling to make sense of life in the booming metropolis of Bangkok, the setting for most of the stories in the collection. In the first, and longest, “Pen in Parentheses”, neither the stylistic flourishes (the story is told in one gigantic set of brackets that contains the entire story, save the first and last few words) nor the characters’ eccentric devotion to Bela Lugosi’s Dracula mask the poignancy of a young man trying to reconcile himself to the loss of his parents and, later, his grandparents.Despite the narrator’s success as an advertising executive — his day-to-day existence is the epitome of modern Bangkok life, complete with funky clothes and a great job — he lives with a sense of confusion as to who he really is. Orphaned as a child and raised by his congee-seller grandfather and schoolteacher grandmother, he knows he has changed, despite his childhood promises to himself never to do so. “Change from what, I can’t remember anymore,” he muses as he finds a scrap of paper from an old school book in his late grandmother’s house.This sense of grappling with material and emotional change — and ultimately failing to understand it — underpins almost all of the stories in The Sad Part Was, and at times it feels as if the author himself is part of a collective effort to understand the rapid evolution of Thailand, and Bangkok in particular, in the two decades straddling the millennium. In “EiPloang”, two strangers meet in Lumpini Park and strike up an unlikely friendship born out of a shared sense of isolation and thinly veiled frustration. Around them, they observe the daily stream of joggers and families out for a stroll, but seem incapable of finding their place in the crowd. Their oddly formal relationship masks deep frustrations with their place as outsiders: the narrator can no longer discern goodness in himself, and can barely form normal, healthy friendships.

The majority of the stories that form this landmark collection — which is not only the first of Yoon’s work to be translated into English, but a rare international publication of Thai fiction — are taken from Yoon’s second book, Kwam Na Ja Pen, which translates roughly as “probability” in mathematical terms. A sensation upon its publication in Thailand in 2002, the book won the SEA Write Prize, Thailand’s top literary honour, and made Yoon a cult figure in Bangkok, where the country’s readership is concentrated.Praised for its linguistic flexibility, with constant plays on words and an unusual use of punctuation, Yoon’s prose exploits the peculiarities of Thai, exploring the disconnect between the written and spoken forms of the language as well as influences drawn from other languages. These textual gymnastics make the translator’s task a nightmare. How fully to convey the richness of “Miss Space,” for example, in which an incipient love affair is viewed through an obsession with the space between words and sentences, if you don’t know that Thai does not employ spaces between the words in a sentence? Mui Poopoksakul’s translation renders the stories fluent and accessible, ironing out the linguistic kinks and allowing Yoon’s portraits of Bangkok lives to take centre stage.In his concentration on the lives of urban dwellers, Yoon also broke the stranglehold of the countryside on the Thai literary imagination. Yet his work shares much of the deep melancholy traditionally attached to writing inspired by rural settings. His characters live with a troubled sense of loss that resists articulation: people and places dear to the narrators are notable by their absence, creating a void that the characters cannot fill. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in “The Crying Parties”, in which four young men in love with the same woman attempt to get over the trauma of her suicide by recreating the chilli-and-cocktail parties they shared when she was alive. In a tragicomic sequence of events, they bribe the new occupant of her apartment; they do everything exactly as they had done before, but are ultimately — inevitably — unable to comprehend their loss. -

Tash Aw

Due to their condensed nature, short stories often rely on novelty to hold attention; whether that be a quirky cast, unusual perspectives or unlikely scenarios. The Sad Part Was, a short collection of tales from celebrated Thai author Prabda Yoon, employs all three to excellent effect.

The very fact that Yoon is bringing a contemporary South East Asian consciousness to a wider audience with this collection (superbly translated by Mui Poopoksakul) contributes to this novelty, but to say it overly depends upon this for its attraction would be hugely unfair. Yoon is never one to shy away from invention, with his stories a playful mixture of pop culture references, abstract concepts and metaphysical self-awareness.

Indeed, in perhaps the most memorable tale from the collection ‘Marut by the Sea’, Yoon calls into question the sagacity of supposedly omniscient authors and their validity in society as a whole. This derisive stance on his own career is an interesting and original exploration of the relevance of writers in a modern world, challenging us to think above and beyond the words on the page.

For a refreshing, engaging respite from the exhaustion of the daily grind, The Sad Part Was is an accomplished balancing act between sadness and silliness, wit and whimsy, wry insight and incisive rhyme. Well worth the few hours it takes to knock the stories out, not least for the fresh perspective they may provide for your own life. - Jonny Sweet

Indeed, in perhaps the most memorable tale from the collection ‘Marut by the Sea’, Yoon calls into question the sagacity of supposedly omniscient authors and their validity in society as a whole. This derisive stance on his own career is an interesting and original exploration of the relevance of writers in a modern world, challenging us to think above and beyond the words on the page.

For a refreshing, engaging respite from the exhaustion of the daily grind, The Sad Part Was is an accomplished balancing act between sadness and silliness, wit and whimsy, wry insight and incisive rhyme. Well worth the few hours it takes to knock the stories out, not least for the fresh perspective they may provide for your own life. - Jonny Sweet

New publisher Tilted Axis Press has made it their mission to publish world literature that ordinarily wouldn’t make it into English translation and shine a light on difference. Prabda Yoon’s short story collection The Sad Part Was certainly showcases both inventive storytelling and an innovative translation process. So much so that the volume carries an afterword by its talented translator, Mui Poopoksakul, which provides some invaluable information regarding the intriguing idiosyncrasies of Thai wordplay and the challenges of rendering these as accurately as possible in English.

As Poopoksakul explains: "any given language is a game with its own internal logic – a challenge for the translator, who attempts to recreate his moves in a language where the rules are different." Apparently, for example, the use of punctuation in Thai is "relatively rare", not to mention the fact that it’s a language that doesn’t utilise spaces between words in the way western readers are used to. Armed with this information, the story Miss Space’ – note the nicely translated wordplay – becomes all the more absorbing. In it, the narrator first takes note of a fellow passenger who is composing diary entries while riding the bus, due to "the extraordinary size" of the spaces between her words: "They catalysed my consciousness as though it had been struck by lightning," the narrator declares, "and I briefly became abnormally perceptive, able to absorb information about my environment instantaneously and effortlessly. Thank god I stopped short of Nirvana." This same wry wit can be heard throughout the collection – Poopoksakul successfully transmuting the mischievousness of Yoon’s original tales, a liveliness that extends to the syntax itself.

As its title suggests, the piece with which the collection opens, Pen in Parentheses, exists entirely within parentheses. The story of the narrator’s life – how he was orphaned as a young boy, subsequently raised by his grandparents, one of the lasting memories of his childhood being his grandfather’s regular Friday night screening of old films, of which the black-and-white version of Dracula, starring Bela Lugosi, was a favourite, something the narrator uses later in life to inspire the advertising campaign (for breath mints – Dracula himself popping a mint in his mouth before he attacks his victim, fangs bared) that sees his career take off – squeezed into the middle of a single sentence: ‘The sheet of paper fell […], so I bent down and picked it up."

Another story, Marut by the Sea, quirkily defies its own creation. "Before it’s too late, may I tell you, dear readers, that my name is not Marut? And I’m not sitting by the sea at all," begins the enraged protagonist, character and author having swapped roles for the duration, the latter taking control, ripping apart the notion of an omnipotent, egotistical author. "There’s this guy," he indignantly continues. "He likes to think that he knows it all. He bosses people around, dreaming up their destinies as though he were God." Yoon is playing with his readers, but we’re in on the joke with him.

Other stories in the collection, however, are more oblique. In Shallow/Deep, Thick/Thin, a traveller stumbles upon "a secret from outer space". He agrees to go on a television talk show in order to divulge his discovery to the world, but the event turns into a media circus of constant commercial breaks, all meaning lost in translation and the presenter’s inability to recognise the real wisdom his guest has to share. Meanwhile, Snow for Mother is a strange but moving tale of parental love; a woman scrimps and saves for years in order to take her son to Alaska in the hope that turning what was once a childhood game between the two of them – the boy daily bringing his mother a handful of imaginary snow – into a reality.

Familial relationships often take centre stage; the values of traditional Thai culture juxtaposed alongside a younger generation clearly torn between the demands of their heritage and increasingly hard to ignore western ways of life. There’s much to delight in here, Yoon’s is an original and innovative voice, and this inviting collection is a welcoming gateway to a new world of narrative possibility. - Lucy Scholes

The Sad Part Was collects a dozen short stories by Prabda Yoon. From the beginning, Prabda keeps readers on their toes, pushing boundaries with the surreal edge and quirkiness to the voice, elements, and episodes in his stories that in other ways also lean heavily (or deceptively) on the seemingly everyday.

In 'Something in the Air' a couple finds two letters from a huge sign flung onto the roof deck of the man's home during a massive storm -- only eventually realizing that there is man, crushed and dead, underneath them. The heavily stylized language the story is presented in -- "What state is the person in ? Approach and inspect", the woman says when they discover the body -- gives a disarmingly formal feel to the absurdity of the situation and the characters' actions. The language and tropes of classical tragedy meet farce in a story of greater, higher powers, and fate and guilt -- the latter poignantly inescapable, even as the young man knows that in his ignorance he was innocent.

The stories range from the as-the-title-has-it The Disappearance of a She-Vampire in Pattaya to the story of a mother taking her now thirty-one-year-old son on a trip to Alaska to finally actually see snow, after a lifetime in which he constantly brought her what he called snow (but apparently was just whatever was at hand -- and, this being Thailand, that was never actually snow). In 'The Crying Parties' four men reunite after the loss of the woman they all loved, holding a 'crying party' of the kind they had with her -- but finding, unsurprisingly, you can't home again (especially when a new tenant has moved in).

Many of the stories play with story-telling itself --beginning with the first: just five words into Pen in Parentheses the narrator gets sidetracked, and nests his story and explanation in parentheses -- which only close again right at then end. The 'story', in its ostensible totality, is the simplest of events and descriptions: "The sheet of paper fell so I bent down and picked it up", but of course the actual story is everything in between.

In 'Marut by the Sea' the protagonist rebels against his creator, spending much of the story complaining about the author --"Prabda Yoon, [...] that's him, that's the guy I'm talking about". And he wants readers to know:

Believe me, Prabda's stories don't get any better than this. I myself could write ten or twenty a day. But I might kill myself first -- it's too easy. The examples I brought up are his specialty. In other words, the type of bizarre story which he makes end so cryptically, as though the harder it is to understand, the better.

In 'Miss Space' the narrator writes about learning to write -- and how, eventually, "after I'd mastered writing (or at least scrawling)"

An up-to-me anarchy prevailed. Without checks or and bounds, the letters became brash -- they got loose, lax and liquidy, lumped together or leaning forwards and backwards in a carefree and shameless manner. The narrator here encounters a woman on a bus, Miss Wondee, who he sees writing in her diary, and he's fascinated by it. As he tries to explain to her: "Your spacing has left a big impression on me". Here is writing where:

One might say that you give as much weight to the spaces as the letters in your sentences. Or maybe even more

While more obvious in the original Thai -- where, as translator Mui Poopoksakul explains in her Afterword, spacing is rather a bigger issue -- there's obvious resonance even in English. And Prabda nicely uses the idea in how he ends this particular tale.

In the opening story, the narrator recounts studying art at university, and notes that simple artistic talent, like being able to draw, isn't enough any more: "You have to think deep. You have to have a 'concept.'". Prabda plays with concepts, but doesn't ignore the craft, either. Translator Mui Poopoksakul's Afterword suggests much of the wordplay -- distinctive to Thai -- is necessarily lost, but enough comes through, or is adequately rendered in English, to give a feel for what Prabda does.

All in all it makes for an enjoyable, playful collection, with some creative ideas nicely realized. - M. A. Orthofer

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.